At the end of the 15th century, following the expulsion of the Jews from Spain and the migration of Jews from Germany to Eastern Europe (mainly to Poland), there was a decline in the proliferation of Hebrew writings. On the other hand, the invention of the printing press in the middle of the 15th century made the Hebrew books much more accessible and thus contributed significantly to the distribution of the language (the first printing houses in the Near East were printing ONLY Hebrew books!)

During the 16th and the 17th centuries, ‘Hebraism’ – the Christian interest in post-biblical Hebrew – began to gain popularity in the Netherlands and Britain.

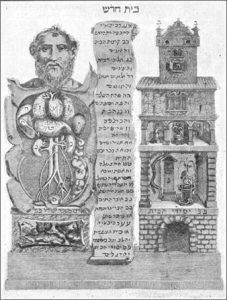

Besides the religious and liturgical literature, which were kept printed all the time, one can also find a diverse informative secular Hebrew literature in the form of dictionaries, different lexicons and even a scientific encyclopedia (printed in Germany in the beginning of the 18th century).

As you have probably noticed, unlike the common (false) assumption, Hebrew was not a dead language at all. It kept evolving and absorbed new terms and vocabulary from several cultures throughout history.

However, it was only at the end of the 18th century when Hebrew entered its new modern phase and regained the prominent position it had once held during ancient times.